70th Anniversary Holodomor

Commemoration in Kyiv

In the spring of 1933, the rural population of Ukraine was dying at a rate of 25,000 a day, half of them children. The land that was known worldwide as the breadbasket of Europe was being ravaged by a man-made famine of unprecedented scale.

It was engineered by Stalin and his hangmen to teach Ukraine’s independent farmers “a lesson they would not forget” for resisting collectivization, which meant giving up their land and livestock to the state. (Ukraine was then under Soviet domination). Moreover, it was meant to deal “a crushing blow” to any national aspirations of the Ukrainian people, 80 percent of whom were peasant farmers.

While millions of men, women and children in Ukraine and in the mostly ethnically Ukrainian areas of the northern Caucasus were dying, the Soviet Union was denying the famine and exporting enough grain from Ukraine to have fed the entire population.

The purpose of this website is twofold:

• To serve as a portal to information about the Holodomor: it’s tragic history and it’s great relevance to today’s world.

• To describe the work of the Connecticut Holodomor Awareness Committee, and how we can help educators and civic organizations host an event as part of your human rights, current awareness, history, or other educational programming.

Only by understanding the genocides of the past, can we hope to prevent others from occurring in our lifetime.

Holodomor Memorial (Kyiv, Ukraine

BRIEF SUMMARY

The term Holodomor refers specifically to the brutal artificial famine imposed by Stalin’s regime on Soviet Ukraine and primarily ethnically Ukrainian areas in the Northern Caucasus in 1932-33.

In its broadest sense, it is also used to describe the Ukrainian genocide that began in 1929 with the massive waves of deadly deportations of Ukraine’s most successful farmers (kurkuls, or kulaks, in Russian) as well as the deportations and executions of Ukraine’s religious, intellectual and cultural leaders, culminating in the devastating forced famine that killed millions more innocent individuals. The genocide in fact continued for several more years with the further destruction of Ukraine’s political leadership, the resettlement of Ukraine’s depopulated areas with other ethnic groups, the prosecution of those who dared to speak of the famine publicly, and the consistent blatant denial of famine by the Soviet regime.

1917

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin take power in Russia.

1922

The Soviet Union is formed with Ukraine becoming one of the republics.

1924

After Lenin’s death, Joseph Stalin ascends to power.

1928

Stalin introduces a program of agricultural collectivization that forces farmers to give up their private land, equipment and livestock, and join state owned, factory-like collective farms. Stalin decides that collective farms would not only feed the industrial workers in the cities but could also provide a substantial amount of grain to be sold abroad, with the money used to finance his industrialization plans.

1929

Many Ukrainian farmers, known for their independence, still refuse to join the collective farms, which they regarded as similar to returning to the serfdom of earlier centuries. Stalin introduces a policy of “class warfare” in the countryside in order to break down resistance to collectivization. The successful farmers, or kurkuls, (kulaks, in Russian) are branded as the class enemy, and brutal enforcement by regular troops and secret police is used to “liquidate them as a class.” Eventually anyone who resists collectivization is considered a kurkul.

1930

1.5 million Ukrainians fall victim to Stalin’s “dekulakization” policies, Over the extended period of collectivization, armed dekulakization brigades forcibly confiscate land, livestock and other property, and evict entire families. Close to half a million individuals in Ukraine are dragged from their homes, packed into freight trains, and shipped to remote, uninhabited areas such as Siberia where they are left, often without food or shelter. A great many, especially children, die in transit or soon thereafter.

1932-1933

The Soviet government sharply increases Ukraine’s production quotas, ensuring that they could not be met. Starvation becomes widespread. In the summer of 1932, a decree is implemented that calls for the arrest or execution of any person – even a child — found taking as little as a few stalks of wheat or any possible food item from the fields where he worked. By decree, discriminatory voucher systems are implemented, and military blockades are erected around many Ukrainian villages preventing the transport of food into the villages and the hungry from leaving in search of food. Brigades of young activists from other Soviet regions are brought in to sweep through the villages and confiscate hidden grain, and eventually any and all food from the farmers’ homes. Stalin states of Ukraine that “the national question is in essence a rural question” and he and his commanders determine to “teach a lesson through famine” and ultimately, to deal a “crushing blow” to the backbone of Ukraine, its rural population.

1933

By June, at the height of the famine, people in Ukraine are dying at the rate of 30,000 a day, nearly a third of them are children under 10. Between 1932-34, approximately 4 million deaths are attributed to starvation within the borders of Soviet Ukraine. This does not include deportations, executions, or deaths from ordinary causes. Stalin denies to the world that there is any famine in Ukraine, and continues to export millions of tons of grain, more than enough to have saved every starving man, woman and child.

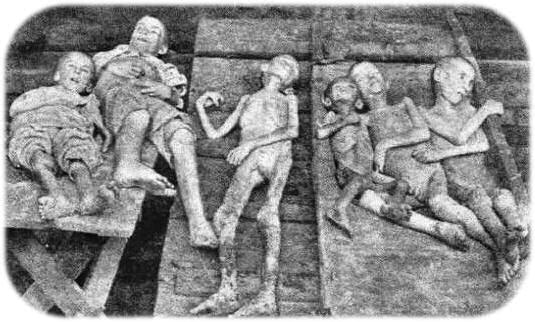

A Corpse of a Famine Victim

on the streets of Kharkiv, 1933.

Uncovering the Truth:

“Any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda. There is no actual starvation or deaths from starvation but there is widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition.”

(as reported by the New York Times correspondent and Pulitzer-prize winner Walter Duranty)

Denial of the famine by Soviet authorities was echoed at the time of the famine by some prominent Western journalists, like Walter Duranty. The Soviet Union adamantly refused any outside assistance because the regime officially denied that there was any famine. Anyone claiming the contrary was accused of spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. Outside the Soviet Union, Western governments adopted a passive attitude toward the famine, although most of them had become aware of the true suffering in Ukraine through confidential diplomatic channels.

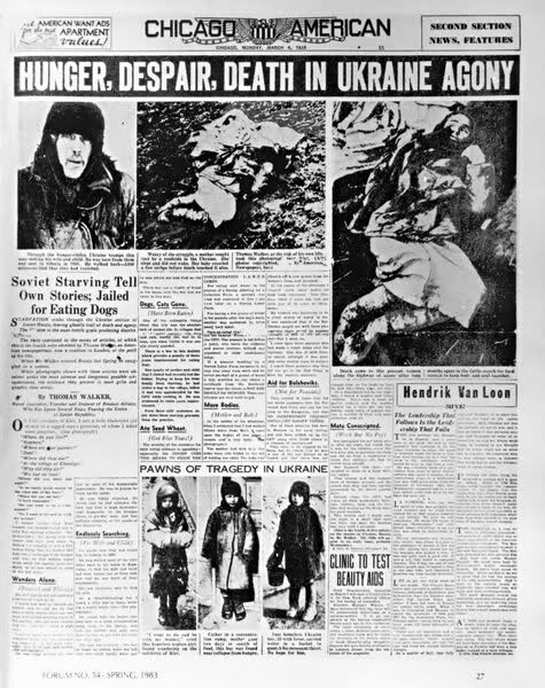

Source: http://lkjhlkjh.weebly.com/evidence.html

In fact, in November 1933, the United States, under newly elected president Franklin D. Roosevelt, chose to formally recognized Stalin’s Communist government and also negotiated a sweeping new trade agreement. The following year, the pattern of denial in the West culminated with the admission of the Soviet Union into the League of Nations. Stalin’s Five-Year Plans for the modernization of the Soviet Union depended largely on the purchase of massive amounts of manufactured goods and technology from Western nations. Those nations were unwilling to disrupt lucrative trade agreements with the Soviet Union in order to pursue the matter of the famine.

In the ensuing decades, Ukrainian émigré groups sought acknowledgment of this tragic, massive genocide, but with little success. Not until the late 1980′s, with the publication of eminent scholar Robert Conquest’s “Harvest of Sorrow,” the report of the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine, and the findings of the International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine, and the release of the eye-opening documentary “Harvest of Despair,” did greater world attention come to bear on this event. In Soviet Ukraine, of course, the Holodomor was kept out of official discourse until the late 1980′s, shortly before Ukraine won its independence in 1991. With the fall of the Soviet Union, previously inaccessible archives, as well as the long suppressed oral testimony of Holodomor survivors living in Ukraine, have yielded massive evidence offering incontrovertible proof of Ukraine’s tragic famine genocide of the 1930′s.

Source: http://lkjhlkjh.weebly.com/evidence.html

On November 28th 2006, the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament of Ukraine) passed a decree defining the Holodomor as a deliberate Act of Genocide. Although the Russian government continues to call Ukraine’s depiction of the famine a “one-sided falsification of history,” it is recognized as genocide by approximately two dozen nations, and is now the focus of considerable international research and documentation.

Eyewitness accounts:

Child victim of Famine/Genocide

Source - http://www.holodomorct.org/index.html

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

George Santayana

“Please return the grain that you have confiscated from me. If you don’t return it I’ll die. I’m 78 years old and I’m incapable of searching for food by myself.”

(From a petition to the authorities by I.A. Rylov)

“I saw the ravages of the famine of 1932-1933 in the Ukraine: hordes of families in rags begging at the railway stations, the women lifting up to the compartment window their starving brats, which, with drumstick limbs, big cadaverous heads and puffed bellies, looked like embryos out of alcohol bottles …”

(as remembered by Arthur Kaestler, a famous British novelist, journalist, and critic. Koestler spent about three months in the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv during the Famine. He wrote about his experiences in “The God That Failed”, a 1949 book which collects together six essays with the testimonies of a number of famous ex-Communists, who were writers and journalists.)

Our father used to read the Bible to us, but whenever he came to the passage mentioning ‘bloodless war’ he could not explain to us what that term meant. When in 1933 he was dying from hunger he called us to his deathbed and said “This, children, is what is called bloodless war…”

(as remembered by Hanna Doroshenko)

“What I saw that morning … was inexpressibly horrible. On a battlefield men die quickly, they fight back … Here I saw people dying in solitude by slow degrees, dying hideously, without the excuse of sacrifice for a cause. They had been trapped and left to starve, each in his own home, by a political decision made in a far-off capital around conference and banquet tables. There was not even the consolation of inevitability to relieve the horror.”

(as remembered by Victor Kravchenko, a Soviet defector who wrote up his experiences of life in the Soviet Union and as a Soviet official, especially in his 1946 book “I Chose Freedom”. “I Chose Freedom” containing extensive revelations on collectivization, Soviet prison camps and the use of slave labor came at a time of growing tension between the Warsaw Pact nations and the West. His death from bullet wounds in his apartment remains unclarified, though it was officially ruled a suicide. His son Andrew continues to believe he was the victim of a KGB execution.)

“From 1931 to 1934 we had great harvests. The weather conditions were great. However, all the grain was taken from us. People searched the fields for mice burrows hoping to find measly amounts of grain stored by mice…”

(as remembered by Mykola Karlosh)

“I still get nauseous when I remember the burial hole that all the dead livestock was thrown into. I still remember people screaming by that hole. Driven to madness by hunger people were ripping the meat of the dead animals. The stronger ones were getting bigger pieces. People ate dogs, cats, just about anything to survive.”

(as remembered by Vasil Boroznyak)

“People were dying all over our village. The dogs ate the ones that were not buried. If people could catch the dogs they were eaten. In the neighboring village people ate bodies that they dug up.”

(as remembered by Motrya Mostova)

“I’m asking for your permission to advance me any amount of grain. I’m completely sick. I don’t have any food. I’ve started to swell up and I can hardly move my feet. Please don’t refuse me or it will be too late.”

(From a petition to the authorities by P. Lube)

“In the spring when acacia trees started blooming everyone began eating their flowers. I remember that our neighbor who didn’t have her own acacia tree climbed on ours and I went to tell my mother that she was eating our flowers. My mother only smiled sadly.”

(as remembered by Vasil Demchenko)

“Of our neighbors I remember all the Solveiki family died, all of the Kapshuks, all the Rahachenkos too – and the Yeremo family – three of them, still alive, were thrown into the mass grave…”

(as remembered by Ekaterina Marchenko)

“Where did all bread disappear, I do not really know, maybe they have taken it all abroad. The authorities have confiscated it, removed from the villages, loaded grain into the railway coaches and took it away someplace. They have searched the houses, taken away everything to the smallest thing. All the vegetable gardens, all the cellars were raked out and everything was taken away.

Wealthy peasants were exiled into Siberia even before Holodomor during the “collectivization”. Communists came, collected everything. Children were crying beaten for that with the boots. It is terrifying to recall what happened. It was so dreadful that every day became engraved in my memory. People were lying everywhere as dead flies. The stench was awful. Many of our neighbors and acquaintances from our street died.

I have no idea how I managed to survive and stay alive. In 1933 we tried to survive the best we could. We collected grass, goose-foot, burdocks, rotten potatoes and made pancakes, soups from putrid beans or nettles.

Collected gley from the trees and ate it, ate sparrows, pigeons, cats, dead and live dogs. When there was still cattle, it was eaten first, then – the domestic animals. Some were eating their own children, I would have never been able to eat my child. One of our neighbours came home when her husband, suffering from severe starvation ate their own baby-daughter. This woman went crazy.

People were drinking a lot of water to fill stomachs, that is why the bellies and legs were swollen, the skin was swelling from the water as well. At that time the punishment for a stolen handful of grain was 5 years of prison. One was not allowed to go into the fields, the sparrows were pecking grain, though people were not allowed.”

(From the memories of Olexandra Rafalska, Zhytomir)

“A boy, 9 years old, said: “Mother said, ‘Save yourself, run to town.’ I turned back twice; I could not bear to leave my mother, but she begged and cried, and I finally went for good.”

(Recollected by an observer simply known as Dr. M.M.)

“At that time I lived in the village of Yaressky of the Poltava region. More than a half of the village population perished as a result of the famine. It was terrifying to walk through the village: swollen people moaning and dying. The bodies of the dead were buried together, because there was no one to dig the graves.

There were no dogs and no cats. People died at work; it was of no concern whether your body was swollen, whether you could work, whether you have eaten, whether you could – you had to go and work. Otherwise – you are the enemy of the people.

Many people never lived to see the crops of 1933 and those crops were considerable. A more severe famine, other sufferings were awaiting ahead. Rye was starting to become ripe. Those who were still able made their way to the fields. This road, however, was covered with dead bodies, some could not reach the fields, some ate grain and died right away. The patrol was hunting them down, collecting everything, trampled down the collected spikelets, beat the people, came into their homes, seized everything. What they could not take – they burned.”

(From the memories of Galina Gubenko, Poltava region)

“The famine began. People were eating cats, dogs in the Ros’ river all the frogs were caught out. Children were gathering insects in the fields and died swollen. Stronger peasants were forced to collect the dead to the cemeteries; they were stocked on the carts like firewood, than dropped off into one big pit. The dead were all around: on the roads, near the river, by the fences. I used to have 5 brothers. Altogether 792 souls have died in our village during the famine, in the war years – 135 souls”

(As remembered by Antonina Meleshchenko, village of Kosivka, region of Kyiv)

“I remember Holodomor very well, but have no wish to recall it. There were so many people dying then. They were lying out in the streets, in the fields, floating in the flux. My uncle lived in Derevka – he died of hunger and my aunt went crazy – she ate her own child. At the time one couldn’t hear the dogs barking – they were all eaten up.”

(From the memories of Galina Smyrna, village Uspenka of Dniepropetrovsk region)

Information*:

*Please click the links below to access event information

New Unit of Study Presented at NERC 2012 Conference

The Holodomor Is Commemorated At The Armenian Library And Museum Of America (ALMA), In Watertown MA.

The latest documentary on the Holodomor: Genocide Revealed

Okradena Zemlia Screening at Litchfield Hills Film Festival (April 2011)

Screening of “Okradena Zemlia” In Hartford and New Haven (November 2010)

Holodomor Exhibit at the University of Connecticut (October-December 2009)

Annual Fundraising Art Show (May 31, 2009)

Commemorative Art Show dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Ukrainian Famine/Gen

http://www.holodomorct.org/index.html

Recommended Resources for Further Information:

http://www.holodomorct.org/links.html

~~~~

Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, set in motion events designed to cause a famine in the Ukraine to destroy the people there seeking independence from his rule. As a result, an estimated 7,000,000 persons perished in this farming area, known as the breadbasket of Europe, with the people deprived of the food they had grown with their own hands.

The Ukrainian independence movement actually predated the Stalin era. Ukraine, which measures about the size of France, had been under the domination of the Imperial Czars of Russia for 200 years. With the collapse of the Czarist rule in March 1917, it seemed the long-awaited opportunity for independence had finally arrived. Optimistic Ukrainians declared their country to be an independent People’s Republic and re-established the ancient capital city of Kiev as the seat of government.

However, their new-found freedom was short-lived. By the end of 1917, Vladimir Lenin, the first leader of the Soviet Union, sought to reclaim all of the areas formerly controlled by the Czars, especially the fertile Ukraine. As a result, four years of chaos and conflict followed in which Ukrainian national troops fought against Lenin’s Red Army, and also against Russia’s White Army (troops still loyal to the Czar) as well as other invading forces including the Germans and Poles.

By 1921, the battles ended with a Soviet victory while the western part of the Ukraine was divided-up among Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. The Soviets immediately began shipping out huge amounts of grain to feed the hungry people of Moscow and other big Russian cities. Coincidentally, a drought occurred in the Ukraine, resulting in widespread starvation and a surge of popular resentment against Lenin and the Soviets.

To lessen the deepening resentment, Lenin relaxed his grip on the country, stopped taking out so much grain, and even encouraged a free-market exchange of goods. This breath of fresh air renewed the people’s interest in independence and resulted in a national revival movement celebrating their unique folk customs, language, poetry, music, arts, and Ukrainian orthodox religion.

But when Lenin died in 1924, he was succeeded by Joseph Stalin, one of the most ruthless humans ever to hold power. To Stalin, the burgeoning national revival movement and continuing loss of Soviet influence in the Ukraine was completely unacceptable. To crush the people’s free spirit, he began to employ the same methods he had successfully used within the Soviet Union. Thus, beginning in 1929, over 5,000 Ukrainian scholars, scientists, cultural and religious leaders were arrested after being falsely accused of plotting an armed revolt. Those arrested were either shot without a trial or deported to prison camps in remote areas of Russia.

Stalin also imposed the Soviet system of land management known as collectivization. This resulted in the seizure of all privately owned farmlands and livestock, in a country where 80 percent of the people were traditional village farmers. Among those farmers, were a class of people called Kulaks by the Communists. They were formerly wealthy farmers that had owned 24 or more acres, or had employed farm workers. Stalin believed any future insurrection would be led by the Kulaks, thus he proclaimed a policy aimed at “liquidating the Kulaks as a class.”

Declared “enemies of the people,” the Kulaks were left homeless and without a single possession as everything was taken from them, even their pots and pans. It was also forbidden by law for anyone to aid dispossessed Kulak families. Some researchers estimate that ten million persons were thrown out of their homes, put on railroad box cars and deported to “special settlements” in the wilderness of Siberia during this era, with up to a third of them perishing amid the frigid living conditions. Men and older boys, along with childless women and unmarried girls, also became slave-workers in Soviet-run mines and big industrial projects.

Back in the Ukraine, once-proud village farmers were by now reduced to the level of rural factory workers on large collective farms. Anyone refusing to participate in the compulsory collectivization system was simply denounced as a Kulak and deported.

A propaganda campaign was started utilizing eager young Communist activists who spread out among the country folk attempting to shore up the people’s support for the Soviet regime. However, their attempts failed. Despite the propaganda, ongoing coercion and threats, the people continued to resist through acts of rebellion and outright sabotage. They burned their own homes rather than surrender them. They took back their property, tools and farm animals from the collectives, harassed and even assassinated local Soviet authorities. This ultimately put them in direct conflict with the power and authority of Joseph Stalin.

Soviet troops and secret police were rushed in to put down the rebellion. They confronted rowdy farmers by firing warning shots above their heads. In some cases, however, they fired directly at the people. Stalin’s secret police (GPU, predecessor of the KGB) also went to work waging a campaign of terror designed to break the people’s will. GPU squads systematically attacked and killed uncooperative farmers.

But the resistance continued. The people simply refused to become cogs in the Soviet farm machine and remained stubbornly determined to return to their pre-Soviet farming lifestyle. Some refused to work at all, leaving the wheat and oats to rot in unharvested fields. Once again, they were placing themselves in conflict with Stalin.

In Moscow, Stalin responded to their unyielding defiance by dictating a policy that would deliberately cause mass starvation and result in the deaths of millions.

By mid 1932, nearly 75 percent of the farms in the Ukraine had been forcibly collectivized. On Stalin’s orders, mandatory quotas of foodstuffs to be shipped out to the Soviet Union were drastically increased in August, October and again in January 1933, until there was simply no food remaining to feed the people of the Ukraine.

Much of the hugely abundant wheat crop harvested by the Ukrainians that year was dumped on the foreign market to generate cash to aid Stalin’s Five Year Plan for the modernization of the Soviet Union and also to help finance his massive military buildup. If the wheat had remained in the Ukraine, it was estimated to have been enough to feed all of the people there for up to two years.

Ukrainian Communists urgently appealed to Moscow for a reduction in the grain quotas and also asked for emergency food aid. Stalin responded by denouncing them and rushed in over 100,000 fiercely loyal Russian soldiers to purge the Ukrainian Communist Party. The Soviets then sealed off the borders of the Ukraine, preventing any food from entering, in effect turning the country into a gigantic concentration camp. Soviet police troops inside the Ukraine also went house to house seizing any stored up food, leaving farm families without a morsel. All food was considered to be the “sacred” property of the State. Anyone caught stealing State property, even an ear of corn or stubble of wheat, could be shot or imprisoned for not less than ten years.

Starvation quickly ensued throughout the Ukraine, with the most vulnerable, children and the elderly, first feeling the effects of malnutrition. The once-smiling young faces of children vanished forever amid the constant pain of hunger. It gnawed away at their bellies, which became grossly swollen, while their arms and legs became like sticks as they slowly starved to death.

Mothers in the countryside sometimes tossed their emaciated children onto passing railroad cars traveling toward cities such as Kiev in the hope someone there would take pity. But in the cities, children and adults who had already flocked there from the countryside were dropping dead in the streets, with their bodies carted away in horse-drawn wagons to be dumped in mass graves. Occasionally, people lying on the sidewalk who were thought to be dead, but were actually still alive, were also carted away and buried.

While police and Communist Party officials remained quite well fed, desperate Ukrainians ate leaves off bushes and trees, killed dogs, cats, frogs, mice and birds then cooked them. Others, gone mad with hunger, resorted to cannibalism, with parents sometimes even eating their own children.

Meanwhile, nearby Soviet-controlled granaries were said to be bursting at the seams from huge stocks of ‘reserve’ grain, which had not yet been shipped out of the Ukraine. In some locations, grain and potatoes were piled in the open, protected by barbed wire and armed GPU guards who shot down anyone attempting to take the food. Farm animals, considered necessary for production, were allowed to be fed, while the people living among them had absolutely nothing to eat.

By the spring of 1933, the height of the famine, an estimated 25,000 persons died every day in the Ukraine. Entire villages were perishing. In Europe, America and Canada, persons of Ukrainian descent and others responded to news reports of the famine by sending in food supplies. But Soviet authorities halted all food shipments at the border. It was the official policy of the Soviet Union to deny the existence of a famine and thus to refuse any outside assistance. Anyone claiming that there was in fact a famine was accused of spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. Inside the Soviet Union, a person could be arrested for even using the word ‘famine’ or ‘hunger’ or ‘starvation’ in a sentence.

The Soviets bolstered their famine denial by duping members of the foreign press and international celebrities through carefully staged photo opportunities in the Soviet Union and the Ukraine. The writer George Bernard Shaw, along with a group of British socialites, visited the Soviet Union and came away with a favorable impression which he disseminated to the world. Former French Premier Edouard Herriot was given a five-day stage-managed tour of the Ukraine, viewing spruced-up streets in Kiev and inspecting a ‘model’ collective farm. He also came away with a favorable impression and even declared there was indeed no famine.

Back in Moscow, six British engineers working in the Soviet Union were arrested and charged with sabotage, espionage and bribery, and threatened with the death penalty. The sensational show trial that followed was actually a cynical ruse to deflect the attention of foreign journalists from the famine. Journalists were warned they would be shut out of the trial completely if they wrote news stories about the famine. Most of the foreign press corp yielded to the Soviet demand and either didn’t cover the famine or wrote stories sympathetic to the official Soviet propaganda line that it didn’t exist. Among those was Pulitzer Prize winning reporter Walter Duranty of the New York Times who sent one dispatch stating “…all talk of famine now is ridiculous.”

http://lkjhlkjh.weebly.com/evidence.html

An announcement published in the newspaper Moloda hvardiya about the village of Pisky being put on the “black list” for failing to provide the specified amount of grain. Source

Outside the Soviet Union, governments of the West adopted a passive attitude toward the famine, although most of them had become aware of the true suffering in the Ukraine through confidential diplomatic channels. In November 1933, the United States, under its new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, even chose to formally recognized Stalin’s Communist government and also negotiated a sweeping new trade agreement. The following year, the pattern of denial in the West culminated with the admission of the Soviet Union into the League of Nations.

Stalin’s Five Year Plan for the modernization of the Soviet Union depended largely on the purchase of massive amounts of manufactured goods and technology from Western nations. Those nations were unwilling to disrupt lucrative trade agreements with the Soviet Union in order to pursue the matter of the famine.

By the end of 1933, nearly 25 percent of the population of the Ukraine, including three million children, had perished. The Kulaks as a class were destroyed and an entire nation of village farmers had been laid low. With his immediate objectives now achieved, Stalin allowed food distribution to resume inside the Ukraine and the famine subsided. However, political persecutions and further round-ups of ‘enemies’ continued unchecked in the years following the famine, interrupted only in June 1941 when Nazi troops stormed into the country. Hitler’s troops, like all previous invaders, arrived in the Ukraine to rob the breadbasket of Europe and simply replaced one reign of terror with another.

Copyright © 2000 The History Place™ All Rights Reserved

http://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/genocide/stalin.htm

~~~

Exhibit G

Sir Winston Churchill to Joseph Stalin:

“…Have the stresses of war been as bad to you personally as carrying through the policy of Collective Farms?”

Stalin:

“ – Oh no, The Collective Farm policy was a terrible struggle… Ten million (he said holding up his hands). It was fearful. Four years it lasted. It was absolutely necessary.”

“Ukrainians are an ethos, with their profound religiosity, individualism, tradition of private property, and devotion to their plots of land, were not suited to the construction of communism, and this fact was noted by the high-ranking Soviet officials.”

Just prior to the Ukrainian genocide, Ukraine was seeking political independence from the Soviet Union. Because the Soviet Union was built on the principles of communism, part of their union seeking independence was very threatening. This is what Stalin was speaking of in this quote. Stalin despised the idea of Ukraine owning private property, and having personal devotion to their land. It was clear the Stalin believed the status of Ukraine was not suited for communism, leading him to make start a famine.

Exhibit H

Quotes by Stalin that exemplify his ruthless ideologies and principles:

Death solves all problems – No man, no problem

One death is a tragedy; one million is a statistic.

Exhibit I

Another quote from Stalin, however this one is much more specific:

“In order to oust the ‘kulaks’ as a class, the resistance of this class must be smashed in open battle and it must be deprived of the productive sources of its existence and development… That is a turn towards the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class”

Exhibit J

“I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying.”

“In a train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung into the spittoon a crust of bread I had been eating from my own supply. The peasant, my fellow passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw orange peel into the peasant again grabbed and devoured it. The Communist subsided.”

- Gareth Jones, Welsh journalist and former Political Secretary of Prime Minister of the U.K., David Lloyd George.

These were the observations he reported in an interview with the New York Evening Post.

He was the first to publicize the famine

http://lkjhlkjh.weebly.com/evidence.html

~~~

Images and Evocations of the Famine-Genocide in Ukrainian Art OF THE FAMINE-GENOCIDE IN UKRAINIAN ART”

[...]As is known, for over fifty years the Communist Party of the USSR vehemently denied that the famine-genocide of 1932-1933 had taken place and attempted to erase it from public consciousness. Speaking out about the famine was ruthlessly punished as an offence against the State. Therefore, there can be no doubt that fear and the urge to survive played an important role in what the artists did or did not do.

I would like to begin by referring to images of the 1921-1922 famine in Ukraine, which were exhibited in the 1920s and later reproduced in books, in order to argue that artists did not avoid the first famine because they did not feel threatened.

One of the most prominent Soviet graphic artists, Vasyl Kasian (1896-1976), while still a student at the Prague Academy of Art, created two images of the 1921-1922 famine. The first is a sepia ink drawing titled “Pieta” (ill. 1). It depicts a grieving mother with the naked, famine ravished body of a child across her knees. The title and the composition echo Michelangelo’s sculpture of the same name where Mary holds the body of Christ in her lap. This relates the secular event to a religious experience.

|

1: Vasyl Kasian. “Pieta,” 1921-1922 |

In the poster “Help the Starving” (Pomozte Hladovejicim) (ill. 2) designed for the Prague Committee helping the famine victims in Ukraine, Kasian painted a peasant mother with emaciated children in an appeal for funds. Painted in oils on board this poster was displayed at the entrance to the Stromovka Park where donations were accepted.[2]

|

2: Vasyl Kasian. “Help the Starving,” 1921-1922 |

After graduation from the Prague Art Academy Kasian returned to Ukraine in 1927. Between 1931-1933 at the height of the forced collectivization and famine Kasian produced woodcuts, which exalted labor and industrialization and ignored what was happening in the countryside. In the woodcut “Bolshevik Harvest,” 1934 (ill. 3), he depicted three happy corpulent figures with lush, fertile fields of grain all around them. These images contradicted the tragic events. They were Kasian’s contribution to the glorification of collectivization and the demands of the Communist Party that “. . . the artistic depiction of reality must be combined with the task of ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism.”[3]

|

3: Vasyl Kasian. “Bolshevik Harvest,” 1934 |

Art produced in Soviet Ukraine of the 1921-1922 famine is scarce. Sofia Nalepinska-Boichuk (1882-1937), the Polish wife of Mykhailo Boichuk and an accomplished artist and teacher, engraved a woodcut titled “Famine” (ill. 4).[4] It shows four emaciated children with swollen bellies being fed by a woman beside a railroad car. Published sources do not provide a provenance of the work, but it appears that the woodcut was first exhibited in 1927 at the Tenth Anniversary of the October Revolution Exhibition.[5] Although Nalepinska was sympathetic to the plight of starving children in 1922, there are no surviving depictions of the famine of 1932-1933 in her work, much of which was destroyed after her arrest and execution in 1937.

|

4: Sofia Nalepinska-Boichuk. “Famine,” 1927 |

[For more information on artist Sofia Nalepinska-Boichuk click on:

http://www.artukraine.com/famineart/nalepynska.htm]

On the basis of these works one can assume that images of famine rendered in the 1920s were permitted and reproduced because they were considered to be the result of bourgeois capitalist oppression of the people.

In my quest for images of the famine-genocide I was able to find only a few works by Kazimir Malevych rendered in response to collectivization and indirectly to famine. These works survived outside of Soviet Ukraine.

Kazimir Malevych (1878-1935), one of the great innovators of the twentieth century and the leading figure of the Russian avant-garde art, was born in Kyiv and brought up in Ukraine. From 1904 to 1926 he worked mostly in Moscow and St. Petersburg/Petrograd/Leningrad where in 1915 he launched Suprematism, the first geometric abstraction movement. After the Bolshevik Revolution, which he supported, he held numerous important positions within the official Communist art establishment. However, in 1926 as a result of art policy changes he was relieved of the directorship of the Institute of Artistic Culture. When political pressures in Russia intensified, he was given refuge in Kyiv and taught at the Kyiv Art Institute from 1928-1930, as did Vladimir Tatlin, the father of Constructivism and a fellow Ukrainian.[6]

About the time of the First Five-Year Plan and the drive to collectivization, Malevych abandoned his Suprematist compositions and returned to painting peasants. However, they were no longer the sturdy peasants of iron and sheet metal of the Cubist period of the 1910s. Often they were faceless and inert puppet-like figures alienated from their surroundings. Those without arms and hands suggest mutilation and helplessness. It has been suggested that Malevych’s return to representational depictions and peasant subject matter was not only prompted by political pressure to return to figuration, but also by his sympathy for the peasants.[7] According to Dmytro Horbachov, a respected art scholar in Kyiv, Malevych visited his sister in Zhytomyr Region every summer and was very distressed by the sight of starvation.[8]

The colored pencil drawing titled “Standing Figure” (ill. 5) (or “Selianyn z khrestamy rozpiattia” [Villager with Crucifixion Crosses] according to D. Horbachov) has been dated as early as 1927 and as late as 1932-33.[9] Thematically and iconographically it is more in keeping with the later works where facial features have been omitted or are indicated by crosses.[10] Here the Orthodox cross if seen only on the face, could be read as a simplification of facial features. However, the repetition of the crosses on the hands and feet suggests a deeper message, perhaps martyrdom. The raised arms echo the Oranta images common in icons. Thus the suffering peasant with arms raised in supplication has spiritual connotations.

|

5: Kazimir Malevych, “Standing Figure,” 1927-1933 |

The pencil drawing “Three Figures” (also known as “Trois personnages marques au visage par: la faucell et le marteau, la croix orthodoxe, un cercueil noir”) has been called “De serp i molot, tam smert’ i holod” (Where There Is the Hammer and Sickle, There Is Death and Famine), 1932-1933 (ill. 6) by D. Horbachov.[11] The latter title corresponds to popular songs of the time, known as “chastushky.”[12] Facial features have been replaced by a hammer and sickle, a cross, and a coffin. This brave indictment of the regime and collectivization survived in the collection of Malevych’s student, Alexandra Leporskaia in Leningrad.

|

6: Kazimir Malevych. “Three Figures,” 1932-1933 |

In the oil on canvas known as “Man Running,” beg. 1930s[13] (ill. 7), Malevych departs from the static frontal peasant figures by painting a figure in motion in a flat barren landscape. Between the symbolic red and white house Malevych has suspended a sword and in front of the running man – a cross. The sword appears dipped in blood and points to a single sack, surely a reference to the brutal confiscation of all grain. The horizontal band on which the figure is running is also red as is the cross. Horbachov has called the work “Selianyn pomizh khrestom i mechem” (Villager between the Cross and the Sword) and has dated the work to 1932-1933.

|

7: Kazimir Malevych. “Man Running,” beg. 1930s |

[For more information on this painting by Malevych click on:

http://www.ArtUkraine.com/paintings/malevich3.htm

http://www.ArtUkraine.com/paintings/malevich4.htm]

Jean-Claude Marcade, a French art historian, writes that “Malevych without a doubt was the only painter who showed the dramatic situation of the Russian peasants at the time of the criminal forced collectivization.”[14] Indeed this appears to be the case. However, I would like to argue that this statement applies especially to Ukrainian peasants as their resistance was widespread and death toll mind-boggling.

Meanwhile in 1932 at the start of the famine the prominent artist, Mykhailo Boichuk (1882-1937), and his colleagues Vasyl Sedliar (1899-1937), Ivan Padalka (1894-1937), and Oksana Pavlenko (1896-1991) were commissioned to decorate the Chervonozavodsk Theatre in Kharkiv. The four huge murals depicted the progress and accomplishments of the First Five-Year Plan in Ukraine. Boichuk was responsible for “Harvest Festival in the Collective Farm” (ill. 8), a large fresco (5.5 x 6 m.) in the central foyer of the theatre. He was forced to make numerous revisions to his sketches to satisfy the authorities, and the work was not completed until 1935. What he painted was a departure from his previous work in terms of style and content.

|

8: Mykhailo Boichuk. “Detail of Harvest Festival on the Collective Farm,” 1935, fresco mural |

[For information on some of the early 1930's artwork by Vasyl Sedliar click on:

http://www.artukraine.com/famineart/sedlyar.htm]

The end product was typical of the demands made on artists by the Communist Party to portray idealized, smiling collective farm workers celebrating the achievements of collectivization and to do so in a realistic three-dimensional manner. It was art custom tailored to hide the gruesome truth and to serve the propaganda purposes of the Soviet state. How ironic that one of the leaders of the Ukrainian artistic renaissance, a dedicated advocate of a national monumental school and the founder of what became known as the Boichukist School was required to do the regime’s bidding to survive. However, even these efforts did not spare him from death.

After the arrest and execution of Padalka, Sedliar, and Boichuk on fabricated charges of membership in a counter-revolutionary terrorist organization, these frescoes, as well as all others done by the Boichukists were destroyed as the work of “enemies of the people.”

As a result, it is perhaps understandable that at the time, fear, trauma and silence overwhelmed all the artists as it did the writers. But eventually, the writers, particularly those who fled Soviet Ukraine for the West, found their voices and recorded their experiences in memoirs or fiction. Why not the artists?

Vasyl Krychevsky and Mykola Nedilko, for example, were professional artists at the time of the famine, yet, they did not commit to paper their eye-witness responses as realistic visual records or transformed metaphorical experiences when they emigrated to the West, as far as I was able to determine.

Mykhailo Dmytrenko, who had worked as an assistant to Fedir Krychevsky at the Kyiv Art Institute and later was active in Canada and the USA, in an interview in 1995 recalled vividly the victims of the famine. He described an emaciated woman with a child in her lap sitting against a wall in Kharkiv, her face covered with flies. The starving child was trying to nurse despite the apparent death of the mother. Visible above them was a poster proclaiming Stalin’s slogan, “Zhyt’ stalo lutshe; zhyt’ stalo vieselieie” (Life Became Better; Life Became Happier).[15]

Dmytrenko did not dare to record what he saw in any drawings or paintings at the time. When I interviewed him, the trauma of working under the Communist regime and his fear of retribution were still very much in evidence even though, at the time, he was 87 years old.

For the thirtieth anniversary of the Famine, in 1963, Dmytrenko painted “1933″ (ill. 9). This was not the horrific image, which was etched in his mind, but a composition where he juxtaposed symbolic images: a famine victim vs. the Communist regime.

|

9: Mykhailo Dmytrenko. “1933,” 1963 |

[Editors Note: ArtUkraine Information Service (ARTUIS) found the original of this painting in the museum at the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA located in South Bound Brook, NJ. ARTUIS was there on Wednesday, December 17, 2003. It was painted in 1963 and is approximately three feet by three feet.]

Another Ukrainian artist working in the USA, Bohdan Pevny, responded to the thirtieth anniversary of the famine with the painting “The Earth” (ill. 10). It shows a dying woman clutching the black earth which had nourished her, but which had been forcibly taken away, as had all grain. Pevny had not witnessed the famine. His depiction was based on a still from Oleksander Dovzhenko’s film Arsenal. Reproductions of The Earth were widely circulated as post cards.

|

10: Bohdan Pevny. “The Earth,” 1963 |

[For more information on this painting by Bohdan Pevny click on:

http://www.ArtUkraine.com/famineart/famine09.htm]

There were responses from other artists who were not witnesses. In 1950 Yuri Kulchytsky in France created a woodcut called Famine “1933″ in an expressionist manner. Yuri Solovij working in New York painted “Pièta: Homage to 1933″ in the American abstract expressionist style in 1953.

Apparently in the diaspora the famine manifested itself in the work of individual artists sporadically usually with the approach of memorial anniversaries. At times it was encouraged by the Ukrainian community. As a direct result of the commemoration of the fiftieth Anniversary of the famine-genocide the Ukrainian Women’s Society in Paris commissioned three Ukrainian artists Omelian Mazuryk, Volodymyr Makarenko, and Anton Solomukha to paint works dedicated to the famine. The work by Makarenko now hangs in the City Hall of the 6th Arrondissement in Paris.[16]

Ukrainian communities in Canada commissioned memorials to be erected in Edmonton and Winnipeg. The memorial monument in Edmonton was designed by Montreal/Toronto artist Ludmyla Temertey. It was inspired by her mother, who was a famine survivor. The one in Winnipeg was the work of Roman Kowal, a local sculptor, who was born in Western Ukraine. As a young man he heard of the famine from one of the survivors. His secular depiction of a mother and child squeezed between two pillars of granite stands in a prestigious location in front of Winnipeg’s City Hall. [For more information on the memorial monument in Winnipeg click on: http://www.artukraine.com/famineart/winnipeg_mon.htm]

In Ukraine, most artists did not turn to the depictions of the famine until Ukraine’s independence. In 1992 to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the famine-genocide “The Ukrainian Great Famine Art Exhibition” was held in Kyiv at the Teachers’ Building (formerly the Central Rada Building at 57 Volodymyrska Street). Over one hundred artists participated.

Vasyl Perevalsky, a Kyiv artist designed the logo for the Great famine Memorial Events in 1993. This became the basis for the monument located in Mykhailivskyi Square near St. Michael of the Golden Domes Church. The design effectively combines the cross with the simplified silhouettes of the Mother of God the Protectress and Child. It was also used on a postage stamp in Ukraine and has become a popular symbol of the famine. [For more information about this artist and the monument in click on: http://www.artukraine.com/famineart/perevalsky.htm, http://www.artukraine.com/famineart/famine22.htm]

In December 2000 the “Great Tragedy and Hope of the Nation Exhibition: Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists” opened in Kyiv with about 500 participants. It appears that the new generations of artists with no direct ties to the famine have shown a heightened awareness and willingness to confront the catastrophic events. Amazingly the format of these large scale exhibits harks back to the big thematic shows that were obligatory during the Soviet period and in which artists participated in great numbers. The deification of the leader, the mythologizing of the revolution, and the glorification of labor have been replaced with representations of formerly forbidden historical events and condemnation of crimes of the Communist state. [For more information about the December 2000 exhibition click on: http://www.artukraine.com/exhibitions/tragedy.htm, http://www.artukraine.com/famineart/famine34]

Of the many artists in Ukraine and in the diaspora who paid homage to the famine-genocide, I would like to single out two: Roman Romanyshyn, a Lviv artist, and Lydia Bodnar-Balahutrak from Houston, Texas.

In 1990 Roman Romanyshyn (1957-) composed a triptych titled “Year 1933.” All three prints are based on the events of Holy Week (Strastnyi tyzhden). In “Thursday” (subtitled Square) (ill. 11) the central figure of Christ is framed within a square format against a black square in the background. The apostles are arranged in four groups of three to form a cross around Christ.

|

11: Roman Romanyshyn, “Year 1933: Thursday,” 1990 |

In the second and central frame “Friday” (subtitled Vertical) (ill. 12) there is a depiction of the Crucifixion with the same apostles arranged in an inverted pyramid. Judas is etched in black.

|

12: Roman Romanyshyn, “Year 1933: Friday,” 1990 |

The third print titled “Saturday” (subtitled Horizontal) (ill. 13) portrays the entombed Christ with the apostles arranged around him. Judas is not only black, but has been turned upside down. The title of the triptych Year 1933 is significant because it provides the key to understanding the artist’s intention of juxtaposing the suffering and death of the Son of God with the suffering and death of innocent Ukrainian victims of the famine. There is no “Sunday.” Romanyshyn does not portray the Resurrection.

|

13: Roman Romanyshyn. “Year 1933: Saturday,” |

Lydia Bodnar-Balahutrak (1953-), a second-generation American, had two extended working trips to Ukraine in 1991 and 1993. Upon her return she felt “a compelling need to document the horrors committed on Ukraine’s people and land.”[17] Two series of works, “Another Kind of Icon and Fragments,” resulted. Both were dominated by themes of humanity and inhumanity, death and rebirth as seen through the prism of tragic historical events in twentieth-century Ukraine.

Several of these works on paper are evocations of the famine incorporating text and photo reproductions, which memorialize the historic events and Bodnar-Balahutrak’s experiences as an artist in the post-modern tradition. According to the artist, “All the works are a personal, visceral piecing together and layering of the spiritual and human dimensions of my cultural identity.”[18]

The mixed media work “Satan All Around Us, Dancing,” 1991 (ill. 14) was an early attempt to come to terms with the overwhelming horrors of the famine and to represent them using painted images, text, political commentary, and symbolic color.

|

14: Lydia Bodnar-Balahutrak. “Satan All Around Us, Dancing,” 1991 |

By 1993 the initial raw emotions and didactic approach had given way to more universal images incorporating appropriated religious art and photocopied photographic material of the actual famine as in “Another Crucifixion” (ill. 15). Here the figure of Christ has been replaced with photocopied images of famine victims. The gold background characteristic of precious icons and sacred spaces stands in stark contrast to images of death.

|

15: Lydia Bodnar-Balahutrak. “Another Crucifixion,” 1993 |

In “Another Kind of Icon #18″ (ill. 16) Bodnar-Balahutrak has appropriated the icon format but has replaced the Mother of God and Christ Child with a photocopied version of an actual starving mother and child. The incorporation of traditional Christian iconography, contemporary documentary evidence and art making, the layering of imagery and meaning have been successfully synthesized to create a powerful after-image of the famine-genocide.

|

16: Lydia Bodnar-Balahutrak. “Another Kind of Icon #18,” 1996 |

It is interesting to note that both Roman Romanyshyn, as well as Vasyl Perevalsky, in Ukraine, and Lydia Bodnar-Balahutrak in America have transcended the apocalyptic subject matter by sublimating the horrors of suffering through the use of Christian symbolism. They have raised their evocations of the famine to the level of the spiritual, thus paying homage to the universal tragedies, which have ravaged our world.

The number of artists who have illuminated the traumatic events of the famine-genocide through their art continues to grow as does the awareness of the famine-genocide. Unfortunately space does not allow me to discuss their work.

In conclusion, I would like to stress that more research needs to be done. I would also like to reiterate that although there is no documentary art contemporary with the famine, compelling after-images of the famine continue to be created. It would appear that the evocations of the famine of 1932-1933 in art created recently serve as a kind of unifying historical reminder of Ukraine’s greatest catastrophe and one of the most brutal genocides in human memory.

FOOTNOTES:

[1]. In 1936 such key figures in Ukrainian art as Mykhailo Boichuk, Ivan Padalka, and Vasyl Sedliar were arrested and shot in 1937. Boichuk’s wife, Sofia Nalepinska-Boichuk, was arrested and executed on December 11, 1937. The wife of Ivan Padalka, Maria Pas’ko, was arrested and sentenced to eight years in the camps. Property of arrested individuals was usually confiscated leaving families destitute. At the beginning of the 1930s the following artists, Boichuk’s students, were arrested and disappeared into Stalin’s GULag: Okhrim Kravchenko, Onufrii Biziukov, Ivan Lypkivsky (executed), and Kyrylo Hvozdyk. Mykola Kasperovych and Yukhym Mykhailiv were also sent to concentration camps where they perished. Hvozdyk returned after Stalin’s death a broken man and refused to discuss his experiences.

[2]. L.Vladych, “Vasyl Kasian” (Kyiv: Mystetstvo, 1978), pp. 71-72.

[3]. For a complete definition of the Socialist Realist method, see “Pervyi Vsesoiuznyi s”ezd sovetskikh pisatelei” [The First All Union Congress of Soviet Writers] Stenographic transcript (Moscow, 1934), p. 716

[4]. This work has been published and exhibited in Canada under the name Hunger. See “The Phenomenon of the Ukrainian Avant-garde 1910-1935″ (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 2001), p. 151.

[5]. Serhii Bilokin, “Holodomor i stanovlennia sotsrealismu yak tvorchoho metodu,” unpublished article, 2003, p. 6.

[6]. In 1930 there was a purge at the Art Institute in Kyiv in which the following artists-professors were ousted: Lev Kramarenko, M. Boichuk, F. Krychevsky, V. Kasian, K. Malevych, and V. Tatlin as “bourgeois specialists”

[7]. Jean-Claude Marcadé in “Malevitch” (Paris: Nouvelles Editions Francaises Casterman, 1990), p. 245.

[8]. In a telephone conversation, March 2003.

[9]. “Malevich Artist and Theoretician” (Paris: Flammarion, 1991), fig. 158 indicates 1927 or later. D. Horbachov in “Khronika 2000,” no. 3-4 (Kyiv 1993), p. 127 gives 1932-33 as the dates. The fact that the work is in the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam and was acquired from Hugo Haring in 1958 makes the earlier date more likely. Jean-Claude Marcadé in “Malevitch,” fig. 379, titles the work “Orant aux stigmates cruciferes orthodoxes” and dates it at the end of 1920s.

[10]. In the painting known as “A Complex Presentiment or A Complex Premonition” dated 1928-32 the figure is shown without facial features, beardless, and without arms. On the reverse Malevych had written “The composition is made up of the elements of emptiness, loneliness and the hopelessness of life in 1913 in Kuntsevo.” The backdating to 1913 is generally interpreted as a safeguard. At the time Malevych painted the work he had lost his status, had been persecuted, and imprisoned briefly in 1930.

[11]. D. Horbachov and O. Naiden, “Malevych muzhyts’kyi,” in “Khronika” 2000, no. 3-4 (Kyiv 1993), p. 226.

[12]. I first learned about “chastushky” (also known as chastivky), popular songs, often couplets, dealing not just with the famine, from Dr. Dagmara Duvirak in Toronto. She heard them from Prof. Mykola Hordiichuk, including ones about the famine. Hordiichuk was a famine survivor and musicologist in Kyiv. D. Horbachov refers to songs about the famine in “The Exuberant World of Ukrainian Avant-garde,” in “The Phenomenon of the Ukrainian Avant-garde 1910-1935,” pp. 37-38. In “Ukrainian Avant-garde Art 1910s-1930s” (Kyiv: Mystetsvo, 1996), p. 5, Horbbachov quotes a specific chastivka, which relates to Malevych’s drawing: “Oi, na khati serp i molot, a u khati – smert’ i holod” [Oh, a sickle and hammer on the house, death and famine in the house].

[13] Marcadé, “Malevitch,” pp. 254 and 257 gives the date as the beginning of the 1930s, whereas D. Horbachov in “Khronika 2000,” dates the work as 1932-33.

[14]. Marcadé, “Malevitch,” p. 245.

[15]. Audio and video interviews were conducted by the author with M. Dmytrenko Nov. 29-30, Dec. 1, 1995 for the Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre in Toronto.

[16]. Makarenko was awarded a silver medal by the City of Paris for this work on June 1, 1987.

[17]. From “Artist’s Statement,” 1996.

[18]. Ibid..

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bilokin, Serhii. “Holodomor i stanovlennia sotsrealismu yak tvorchoho metodu” (The Famine and the Establishment of Socialist Realism). Unpublished article, 2003.

Contanza, Mary S. “The Living Witness. Art in the Concentration Camps and Ghettos.” New York: Free Press, 1982.

Horbachov, Dmytro. Ukrainian Avant-garde Art 1910s-1930s. Kyiv: Mystetstvo, 1996.

Horbachov, D. and O. Naiden. “Malevych muzhyts’kyi”, Khronika 2000. (Kyiv, 1993, no. 3-4).

“Kazimir Malevich 1878-1935.” Los Angeles: The Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, 1990.

“Malevich. Artist and Theoretician,” Paris: Flammarion, 1991

Marcade, Jean-Claude. “Malevitch,” Nouvelles Editions Francaises Casterman, 1990.

“Pervyi Vsesoiuznyi sezd sovetskikh pisatelei.” Stenographic transcript. Moscow, 1934.

“The Phenomenon of the Ukrainian Avant-garde 1910-1935,” Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 2001

Ripko, Olena. “Boichuk i Boichukisty, Boichukizm.” Lviv: Lvivska Kartynna Halereia, 1991.

Ripko, Olena. “U poshukakh strachenoho mynuloho.” Lviv: Kameniar, 1996.

This article posted by the ArtUkraine.com Information Service (ARTUIS) with permission from author Daria Darewych and from publisher Charles Schlacks. Information cannot be reproduced without permission.

The material composed, edited and posted with identified inserts of additional information by the ArtUkraine.com Information Service (ARTUIS). Specific information from ARTUIS can only be used with permission.

FOR PERSONAL AND ACADEMIC USE ONLY.

Copies of “HOLODOMOR: THE UKRAINIAN GENOCIDE, 1932-1933″ Holodomor 70th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, Canadian-American Slavic Studies Journal, can be ordered from the publisher via the following contact information. The price of this special edition is: $5.00, plus $2.00 US postage, $3.00 in Canada, and $4.00 foreign. Mr. Charles Schlacks, Jr., Publisher, P. O.Box 1256, Idyllwild, CA 92549-1256 USA, schslavic@tazland.net

HOLODOMOR: THE UKRAINIAN GENOCIDE, 1932-1933

Canadian-American Slavic Studies Journal

Holodomor 70th Anniversary Commemorative Edition

Mr. Charles Schlacks, Jr, Publisher

Idyllwild, CA, Vol. 37, No. 3, Fall 2003

The Fall 2003 Canadian-American Slavic Studies journal features the following articles:

Foreword: “1933. Genocide. Ten Million. Holodomor,” by Peter Borisow, President of the Hollywood Trident Foundation and the Genocide Awareness Foundation. Mr. Borisow’s article focuses on the fact that it is necessary to correct the erroneous perception that Holodomor was a weather-generated event, as is the common public perception gained through the use of the term, “famine.”

Margaret Siriol Colley and Nigel Linsan Colley wrote, “Gareth Jones: A Voice Crying in the Wilderness,” an article based on the British reporter Gareth Jones’ articles (including those that first broke the news of the Holodomor to the west), diaries, and letters, as well as official British government documents, and letters from former Prime Minister, David Lloyd George.

Dr. Daria Darewych’s article, “Images and Evocations of the Famine-Genoide in Ukrainian Art,” is enhanced by 16 exemplary illustrations. Dr. Darewych is the President of the Shevchenko Society of Canada, and is a Professor of Art History at York University. Her article explains the reasons why, because of the political oppression pervasive in the USSR, there was, of political necessity, a dearth of artistic images dealing with the Holodomor until the recently achieved freedom of expression permitted the subject to be artistically addressed.

Dr. James E. Mace, Professor of Political Science at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy National University contributed his article, “Is the Ukrainian Genocide a Myth?” Citing Stalin’s letter to Kaganovich of 11 September 1932, he points out the unquestionable fact that the genocidal aspects of the Holodomor were both known and condoned at the highest level of the Stalinist regime.

Johan Ohman, a Ph.D. candidate at Lund University in Sweden, addresses the ways in which Ukrainian subjugation by the USSR especially as demonstrated by the ravages inflicted upon the populace by the Holodomor influenced the formation of both national and personal identities. He also discusses how these subjects, as well as Ukrainian history in general, are presented in Ukrainian textbooks.

“The Holodomor of 1932-1933, as Presented in Drama and the Issue of Blame,” by Dr. Larissa M. L. Zaleska Onyshkevych, President of the Shevchenko Society of America, explores the Holodomor-related works of the playwrights, Yuriy Yanovskyi, Serhiy Kokot-Ledianskyi, and Bohdan Boychuk. As with visual arts, the problem of Soviet control of all aspects of life prohibited these writers, and others, to present the Holodomor in its horrible truth and vastness. While in the thrall of the Soviet Union, these writers could mention the ravages of the Holodomor only through the use of veiled allusions, or in publications written by the Diaspora and/or published in the west. Once the collapse of the Soviet Union removed the threat of fast and sure reprisals against the artist, his work, and his family members, artists and writers were freed to relate the once-captive history of their people.

Orysia Paszeczak Tracz translated primary source testimonies from the book edited by Lidia Borysivna Kovalenko and Volodymyr Antonovych, Holod 33: A National Memorial Book. Mrs. Tracz is an Ukrainian ethnographer, translator, and frequent contributor to The Ukrainian Weekly. The variety, and yet universality of experiences suffered by those providing testimonies for this book express the profound influence of the terrors these people witnessed and never forgot.

“The Holodomor: 1932-1933,” provides an overview of the Holodomor, and makes use of a variety of international and multi-ethnic sources to support its various points. The Introduction is, “A Selective Annotated Bibliography of Books in English Regarding the Holodomor and Stalinism,” and there is a review of the book of primary source famine-appeal letters, We’ll Meet Again in Heaven: German-Russians Write Their American Relatives, 1925-1937, by Ronald J. Vossler.

Copies of Holodomor: The Ukrainian Genocide, 1932-1933 can be ordered from the publisher via the following contact information. The price of this special edition is: $5.00, plus $2.00 US postage, $3.00 in Canada, and $4.00 foreign.

Mr. Charles Schlacks, Jr., Publisher, P. O. Box 1256,

Idyllwild, CA 92549-1256 USA, schslavic@tazland.net

~~~~~

“…Denial of the Holodomor (Ukrainian: Заперечення Голодомору, Russian: Отрицание Голодомора) is the assertion that the 1932-1933 Holodomor, a supposedly artificial famine in Soviet Ukraine,[1] recognized as a crime against humanity by the European Parliament,[2] did not occur.[3][4][5][6]

This denial and suppression was made in official Soviet propaganda from the very beginning and until the 1980s. It was supported by some Western journalists and intellectuals.[4][5][7][8][9] It was echoed at the time of the famine by some prominent Western journalists, including Walter Duranty and Louis Fischer. The denial of the famine was a highly successful and well orchestrated disinformation campaign by the Soviet government.[3][4][5] Stalin “had achieved the impossible: he had silenced all the talk of hunger… Millions were dying, but the nation hymned the praises of collectivization”, said historian and writer Edvard Radzinsky.[5]

According to Robert Conquest, that was the first major instance of Soviet authorities adopting Hitler’s Big Lie propaganda technique to sway world opinion, to be followed by similar campaigns over the Moscow Trials and denial of the Gulag labor camp system.[10]

The famine’s existence is still disputed by some, despite a general consensus. The causes, nature and extent of the Holodomor remain topics of controversy and active scholarship.

Soviet Union Cover-up of the famine

Soviet leadership undertook extensive efforts to prevent the spread of any information about the famine by keeping state communications top secret and taking other measures to prevent word of the famine from spreading. When Ukrainian peasants traveled north to Russia seeking bread, Joseph Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov sent a secret telegram to the party and provincial police chiefs with instructions to turn them back,[11] alleging Polish agents were attempting to create a famine scare. OGPU chairman Genrikh Yagoda subsequently reported that over 200,000 peasants had been turned back.

Stalin’s wife, Nadezhda Allilueva, learned about the famine from Ukrainian students at the technical school she was attending. They described acts of cannibalism[12] and bands of orphaned children. Allilueva complained to Stalin, who then ordered the OGPU to purge all the college students who had taken part in collectivization.[13]

Soviet President Mikhail Kalinin responded to Western offers of food by telling of “political cheats who offer to help the starving Ukraine,” and commented that, “only the most decadent classes are capable of producing such cynical elements.”[6][14]

In an interview with Gareth Jones in March 1933, Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov stated, “Well, there is no famine”, and went on to say, “You must take a longer view. The present hunger is temporary. In writing books you must have a longer view. It would be difficult to describe it as hunger.”[15]

On instructions from Litvinov, Boris Skvirsky, embassy counselor of the recently opened Soviet Embassy in the United States, published a letter on January 3, 1934, in response to a pamphlet about the famine.[16] In his letter, Skvirsky stated that the idea that the Soviet government was “deliberately killing the population of the Ukraine” “wholly grotesque.” He claimed that the Ukrainian population had been increasing at an annual rate of 2 percent during the preceding five years and asserted that the death rate in Ukraine “was the lowest of that of any of the constituent republics composing the Soviet Union”, concluding that it “was about 35 percent lower than the pre-war death rate of tsarist days.”[17]

Mention of the famine was criminalized, punishable with a five-year term in the Gulag labor camps. Blaming the authorities was punishable by death.

Falsification and suppression of evidence

The true number of dead was concealed. At the Kiev Medical Inspectorate, for example, the actual number of corpses, 9,472, was recorded as only 3,997. The GPU was directly involved in the deliberate destruction of actual birth and death records, as well as the fabrication of false information to cover up information regarding the causes and scale of death in Ukraine.[18] Similar falsifications of official records were widespread.[6]

The January 1937 census, the first in 11 years, was intended to reflect the achievements of Stalin’s rule. It became evident that population growth particularly in Ukraine failed to meet official targets—evidence of the mortality resulting from the famine and from associated indirect demographic losses. Those collecting the data, senior statisticians with decades of experience, were arrested and executed, including three successive heads of the Soviet Central Statistical Administration. The census data itself was locked away for half a century in the Russian State Archive of the Economy.[19][20]

The subsequent 1939 census was organized in a manner that certainly inflated data on population numbers. It showed a population figure of 170.6 million people, manipulated so as to match the numbers stated by Joseph Stalin in his report to the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party that March. No other census in the Soviet Union was conducted until 1959.

Campaigns of disinformation

The Soviet Union denied all existence of the famine until its 50th anniversary, in 1983, when the world-wide Ukrainian community coordinated famine remembrance. The Ukrainian diaspora exerted significant pressure on the media and various governments, including the United States and Canada, to raise the issue of the famine with the government of the Soviet Union.

While the Soviet government admitted that some peasantry died, it also sought to launch a disinformation campaign, in February 1983, to blame drought. The head of the directorate for relations with foreign countries for the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), A. Merkulov, charged Leonid Kravchuk, the chief idealogue for the Communist Party in Ukraine, with finding rainfall evidence for the Great Famine. This new evidence was to be sent to the Novosti press centers in the U.S. and Canada, denouncing the “antidemocratic base of the Ukrainian bourgeois Nationalists, the collaboration of the Banderists and the Hitlerite Fascists during the Second World War.”[21] Kravchuk’s inquiry into the rainfalls for the 1932-1933 period found that they were within normal parameters.[22] Nevertheless, the official position regarding drought did not change.

The United States Congress created the Commission on the Ukraine Famine in 1986. Soviet authorities were correct in their expectation that the commission would lay responsibility for the famine on the Soviet state.[23]

Increased international awareness of the famine did not dissuade Soviet authorities from further disinformation in anticipation of the 55th anniversary of the famine. In Canada, the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians (a cultural and educational organization founded in 1918 and still preserving its original pro-Communist leanings) published numerous articles denying the famine in its publications, available to the public through its bookstore outlets. In 2007, newly released correspondence confirmed instructions for the content of these materials had come directly from Soviet authorities.

Ultimately, as President of Ukraine, Kravchuk exposed the official cover-up attempts and came out in support of recognizing the famine, named the “Holodomor,”[24] as genocide.

From glasnost to post-Soviet standoff

In an open letter to Mikhail Gorbachev in August 1987, veteran dissident Viacheslav Chornovil wrote about the denial of the famine:[25]

“The biggest and most infamous blank spot in the Soviet history of Ukraine is the hollow silence for over 50 years about the genocide of the Ukrainian nation organized by Stalin and his henchmen … The Great Famine of 1932-33, which took millions of human lives. In one year—1933—my people lost more than throughout all of World War II, which ravaged our land.”

It was during this period of glasnost that Soviet authorities admitted that agricultural policies played a direct role in the causing the famine.

In the post Soviet era, an independent Ukraine has officially condemned the Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people. The Russian Foreign Ministry counters that not only Ukrainians died in the Great Famine, that to single out Ukrainians as victims insults others who died, that the

- “declaration of the tragic events of that time as act of genocide against the Ukrainian nation is a unilateral misinterpretation of history in favor of modern conformist political and ideological principles.”

WALTER DURANTY and THE NEW YORK TIMES

According to Patrick Wright,[27] Robert C. Tucker,[28] Eugene Lyons,[29] Mona Charen[30] and Thomas Woods [31] one of the first Western Holodomor deniers was Walter Duranty, the winner of the 1932 Pulitzer prize in journalism in the category of correspondence, for his dispatches on Soviet Union (called incorrectly Russia) and the working out of the Five Year Plan.[32] While the famine was raging, he wrote in the pages of The New York Times that “Any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda”, and that “There is no actual starvation or deaths from starvation, but there is widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition.”[29]

In his reports, Duranty downplayed the impact of food shortages in Ukraine, although in private he told Eugene Lyons and reported to the British Embassy that the population of Ukraine and Lower Volga had “decreased” by six to seven million.[33] While other Western reporters reported the famine conditions as best they could due to Soviet censorship and restrictions on visiting areas affected by the famine, Duranty’s reports frequently echoed the official Soviet view. As Duranty wrote in a dispatch from Moscow in March 1933, “Conditions are bad, but there is no famine… But—to put it brutally—you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”[34]

Duranty wrote articles denying that the Holodomor was taking place in Ukraine. He also wrote denunciations of those who wrote about the famine, accusing them of being reactionaries and anti-Bolshevik propagandists. Duranty repeated Soviet propaganda without verifying its veracity. As the New York Times notes: “Taking Soviet propaganda at face value this way was completely misleading, as talking with ordinary Russians might have revealed even at the time.”[34]

In August 1933, Cardinal Theodor Innitzer of Vienna called for relief efforts, stating that the Ukrainian famine was claiming lives “likely… numbered… by the millions” and driving those still alive to infanticide and cannibalism. The New York Times, August 20, 1933, reported Innitzer’s charge and published an official Soviet denial: “in the Soviet Union we have neither cannibals nor cardinals”. The next day, the Times added Duranty’s own denial.

[German-language source, Hungersnot! (Famine Calamity) by Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, dated approximately 1934 and published in Vienna by Buchdruckerei Karolik consists of eyewitness accounts of German nationals - religious leaders as well as businessmen, who were in Ukraine at that time. It also includes a map (and pictures) of the famine-afflicted areas of Ukraine. Source

Genocide Photo's - from Theodor Cardinal Innitzer's Archive: Source

Some historians consider Duranty’s reports from Moscow to be crucial in the decision taken by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to grant the Soviet Union diplomatic recognition in 1933.[35] Bolshevik Karl Radek said that was indeed the case.[4]

Louis Fischer and The Nation

Next to Duranty, the American reporter most consistently willing to gloss Soviet reality was Louis Fischer, who had a deep ideological commitment to Soviet communism dating back to 1920. When Fischer traveled to Ukraine in October and November 1932, for The Nation, he was alarmed at what he saw. “In the Poltava, Vinnitsa, Podolsk and Kiev regions, conditions will be hard”, he wrote, “I think there is no starvation anywhere in Ukraine now — after all they have just gathered in the harvest, but it was a bad harvest.”

Initially critical of the Soviet grain procurement program because it created the food problem, Fischer by February 1933 adopted the official Soviet government view, which blamed the problem on Ukrainian counter-revolutionary nationalist “wreckers.” It seemed “whole villages” had been “contaminated” by such men, who had to be deported to “lumbering camps and mining areas in distant agricultural areas which are now just entering upon their pioneering stage.” These steps were forced upon the Kremlin, Fischer wrote, but the Soviets were, nevertheless, learning how to rule wisely.

Fischer was on a lecture tour in the United States when Gareth Jones’ famine story broke. Speaking to a college audience in Oakland, California, a week later, Fischer stated emphatically: “There is no starvation in Russia.” He spent the spring of 1933 campaigning for American diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union. As rumors of a famine in the USSR reached American shores, Fischer vociferously denied the reports.

Fischer’s article entitled “Russia’s Last Hard Year”, stated, “The first half of 1933 was very difficult indeed. Many people simply did not have sufficient nourishment.” Fischer blamed poor weather and the refusal of peasants to harvest the grain, which then rotted in the fields. Government requisitions drained the countryside of food, he admitted, but military needs (a potential conflict with Japan) explained the need for such deadly thoroughness in grain collections.[40]